Courtois Cornets History

Most of the Courtois family biographical information below comes directly from the excellent and exhaustive article, “COURTOIS, LA DYNASTIE ENFIN RETROUVÉE!” by Maxime and Chrisian Chagot, published in LARIGOT number 54, December 2014. Much of this has also been condensed and clarified in the first two chapters of “TRUMPETS AND OTHER HIGH BRASS”, volume 4, by Sabine Klaus, published by the National Music Museum, 2022. However, the bulk of the content below concerns the British and American market, where Antoine Courtois sold most of his production and the mechanics of the instruments.

Born in Paris March 22nd, 1814, Denis Antoine Courtois was from a metalworking family going back at least five generations. His great great great grandfather was a boilermaker in Villenauxe in the 17th century, making and repairing distilling equipment used in the winemaking industry. Utilizing their knowledge of making tubing and vessels from copper and brass, his two great uncles, Louis Nicolas and Adrien Courtois, likely with the help of his grandfather, Antoine Laurent (elder), started making brass musical instruments in the late 18th century. His uncle, Antoine Laurent (younger) established a shop on rue des Prouvaires in Paris for making horns in the style of Raoux and was joined by his brother, Denis Victor, Denis Antoine’s father, using the name “Courtois frère(s)”. They moved to 21 rue du Caire sometime before 1819, and in addition to horns, were soon making trumpets, bugles, trombones, keyed bugles and ophicleides.

Click on images for larger views.

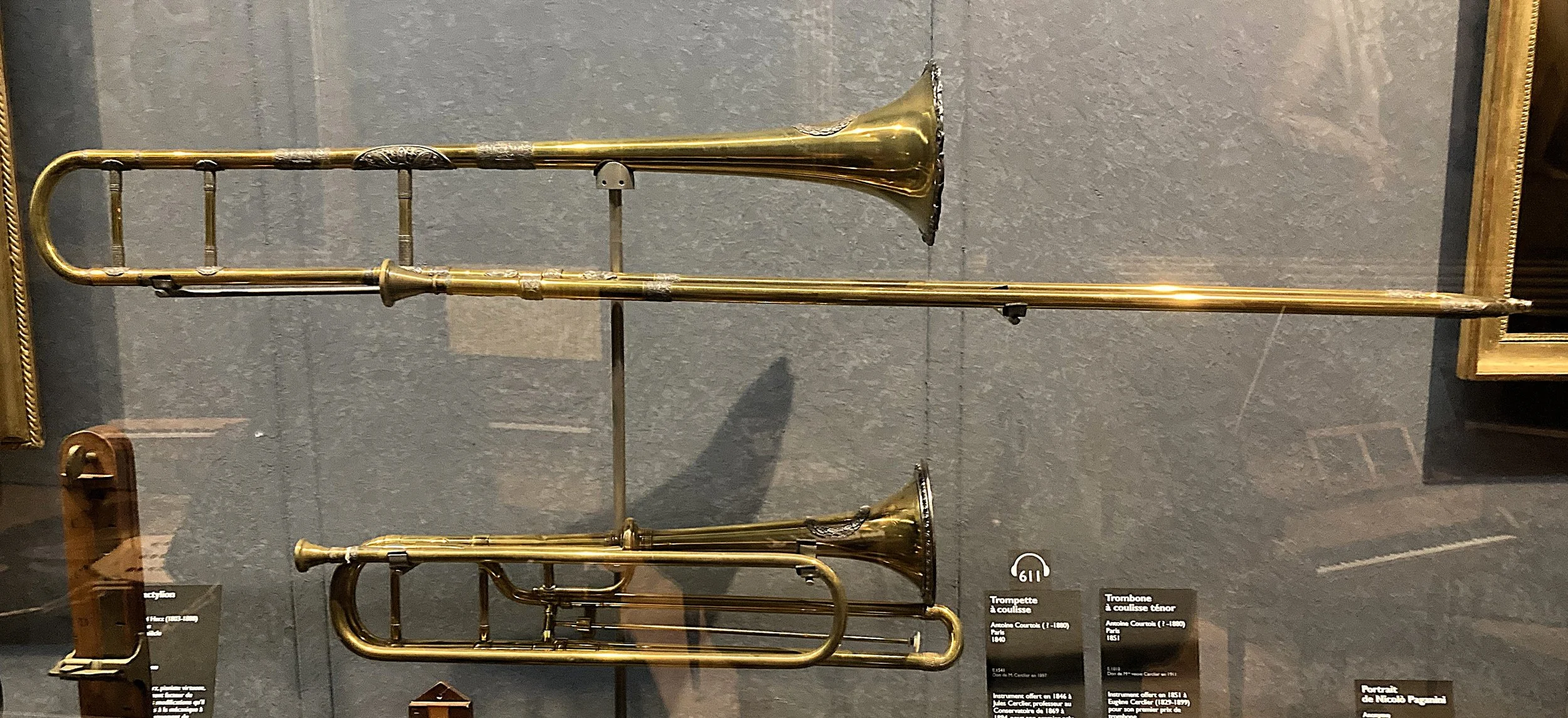

In 1823 Antoine Laurent designed the clairon to be used by the military as a replacement for the trumpet and with a sound that was thought to be distinct from the British and German bugles. In the 1830s, they began to make horns and cornets using the newly available Stölzel valves and they were among the first (along with Halary, Labbaye and Sax) to utilize the newly designed Périnet valves made under license by Sasasigne in late 1838. Starting in about 1843, they stamped on the bells “Fourisseur (or Facteur) du Conservatoire” below their name “Courtois Frères”. As early as 1838 a trombone made by Courtois Freres was awarded to the student who won the solo competition at the Conservatoire de Paris. Cornets were included in the curriculum starting in 1848.

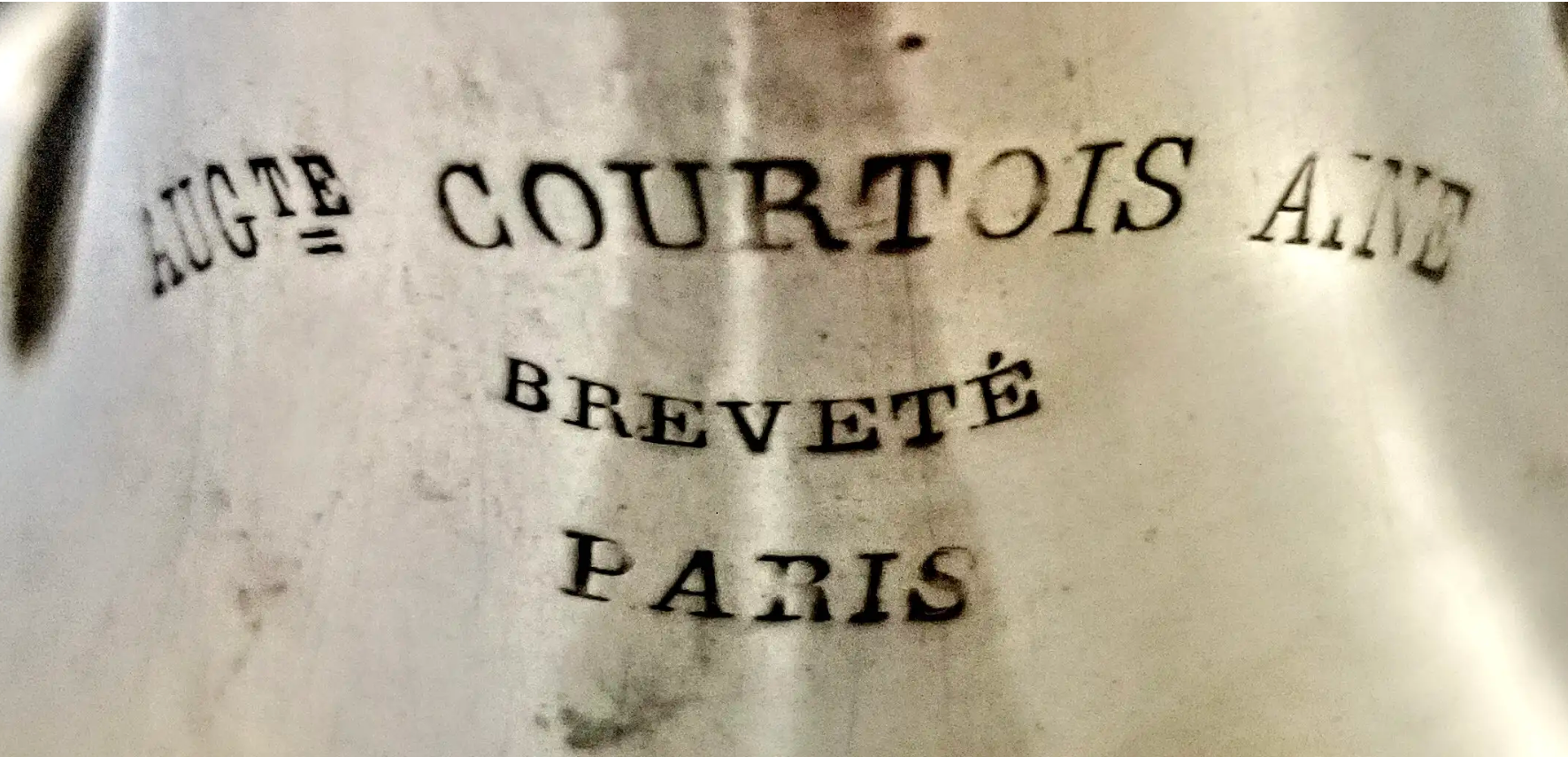

Other Courtois family members that became brass instrument makers were Denis Antoine’s uncles Adrien Noël and Rose, who were sons of his great uncle Adrien. Adrien Noël started making instruments in Montmirail, possibly with his brother Rose, and then in Paris, in 1812 at 34 Street des Vieux-Augustins. He stamped his products with the name “Courtois neveu aîné”. By the early 1830s, he was joined in Paris by Rose and retired by 1835, leaving the business to Rose. At this time, Rose changed the name stamp to “Courtois neveu”. Rose retired in 1840, leaving the business to his three sons, Auguste, Louis, and Eugène Joseph, who called their shop “Les trois fils de Courtois”. Within a few years, they separated and Auguste marked his instruments “AUG’te. COURTOIS AINÉ / BREVETÉ / PARIS” and Eugène marked his “Eugène Courtois jeune”. No instruments are known from Louis Courtois in Paris.

After the retirement of his uncle and the death of his father in 1844, Denis Antoine took over the business and changed the name to “Antoine Courtois”. He continued making cornets with both Stölzel and Périnet piston valves based on the designs of Périnet, Labbaye, Halary and other Parisian makers as well as horns, trombones and other instruments made by the previous firm. His renown for trombones and orchestral trumpets was almost as large as for cornets throughout the 19th century. He won an “Honorable Mention” prize medal at London’s Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851 for a display of instruments that included cornets, trumpets, keyed bugles, trombones, and ophicleides.

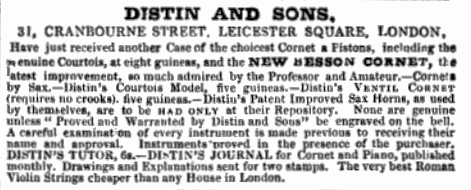

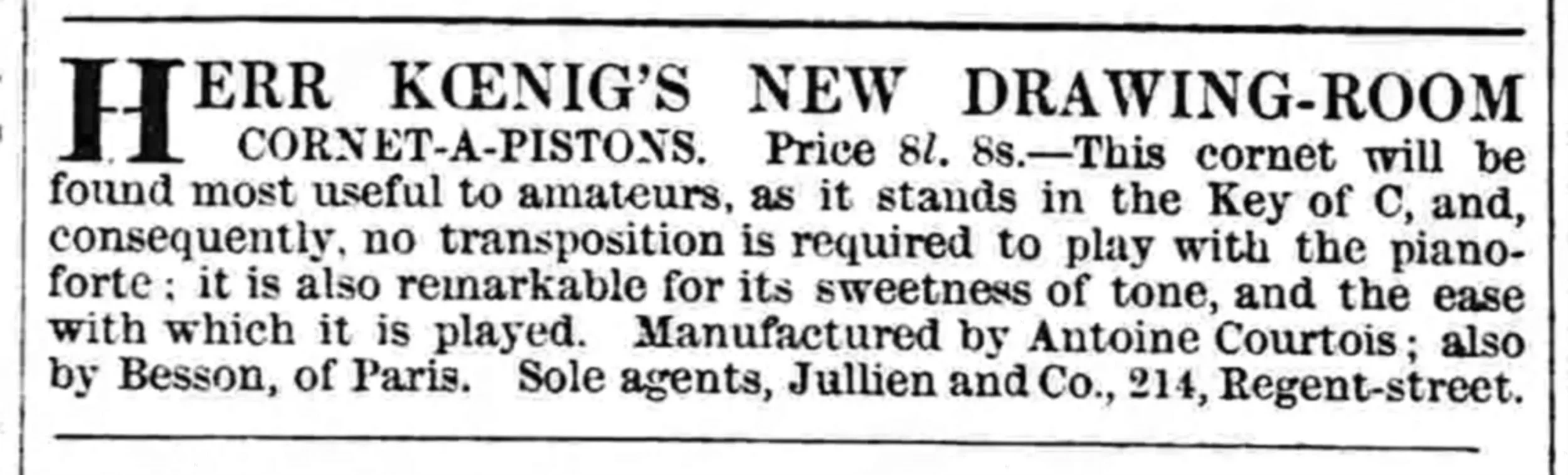

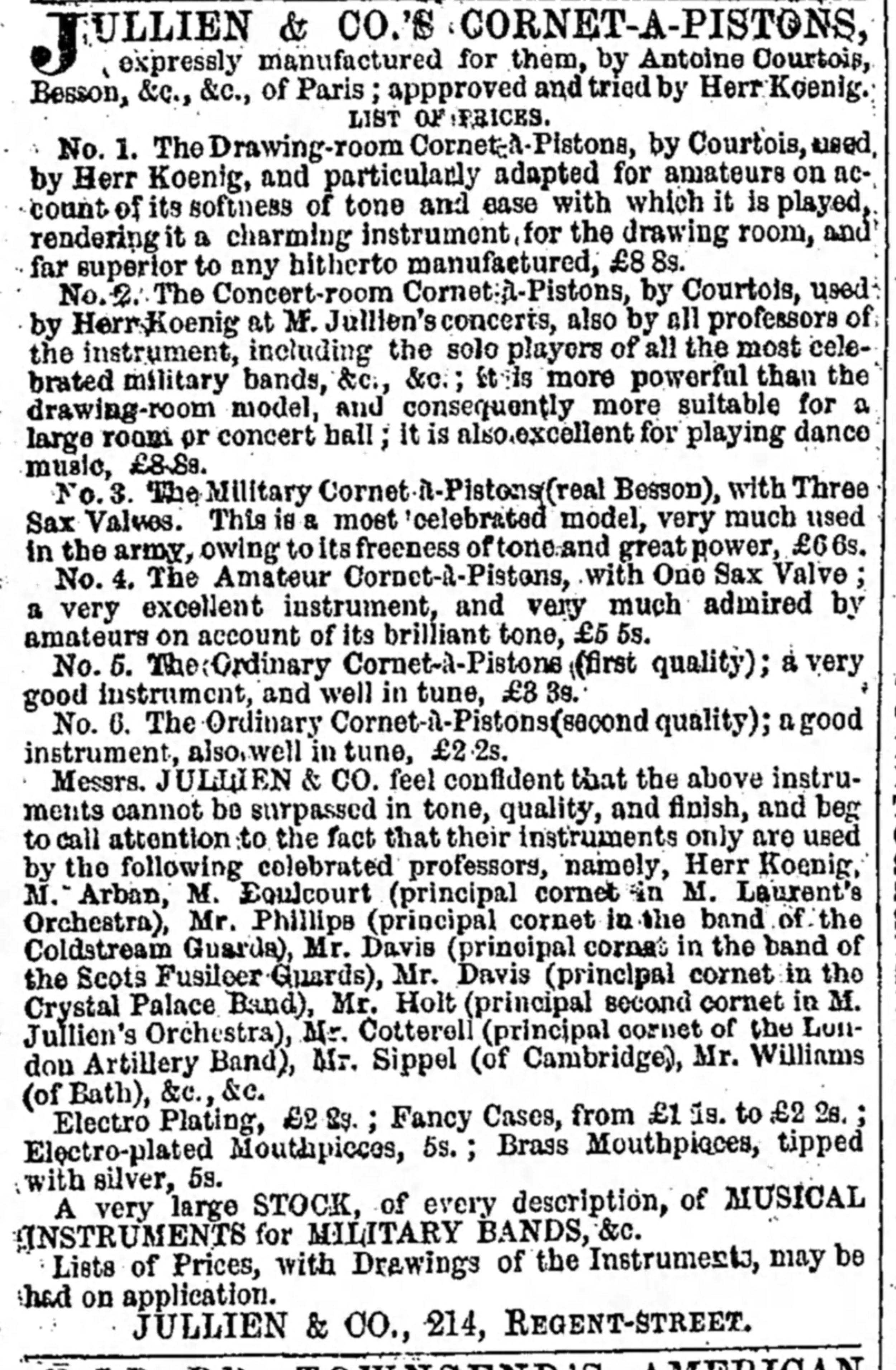

Even before the 1851 exhibition, Courtois cornets were establishing a reputation in England. In August 1845, “Courtois Cornopeans” were advertised as available from London dealer Wolf & Figg: “Musical Instrument Manufacturers and Importers, having been appointed SOLE AGENTS in the United Kingdom for the SALE of the above justly celebrated Instruments, patronized by Herr Koenig”. Also, Distin & Co. started advertising in February of 1848 in The Musical World. They announced the availability of “the choicest Cornet á Pistons, including the genuine Courtois, at eight guineas, and the NEW BESSON CORNET”, along with “Distin’s Courtois Model, five guineas”. The latter was likely made for them by Gautrot (the largest maker at the time) or another French maker, more proof of the desirability of the Courtois name and the instruments made by them. It is interesting to note that this was six or seven years before the introduction of the “New Model”, a unique design that was copied by most makers thereafter, including Henry Distin by the 1860s. In 1848, both Courtois and Besson were still making cornets that followed design patterns that had been set by other Parisian makers.

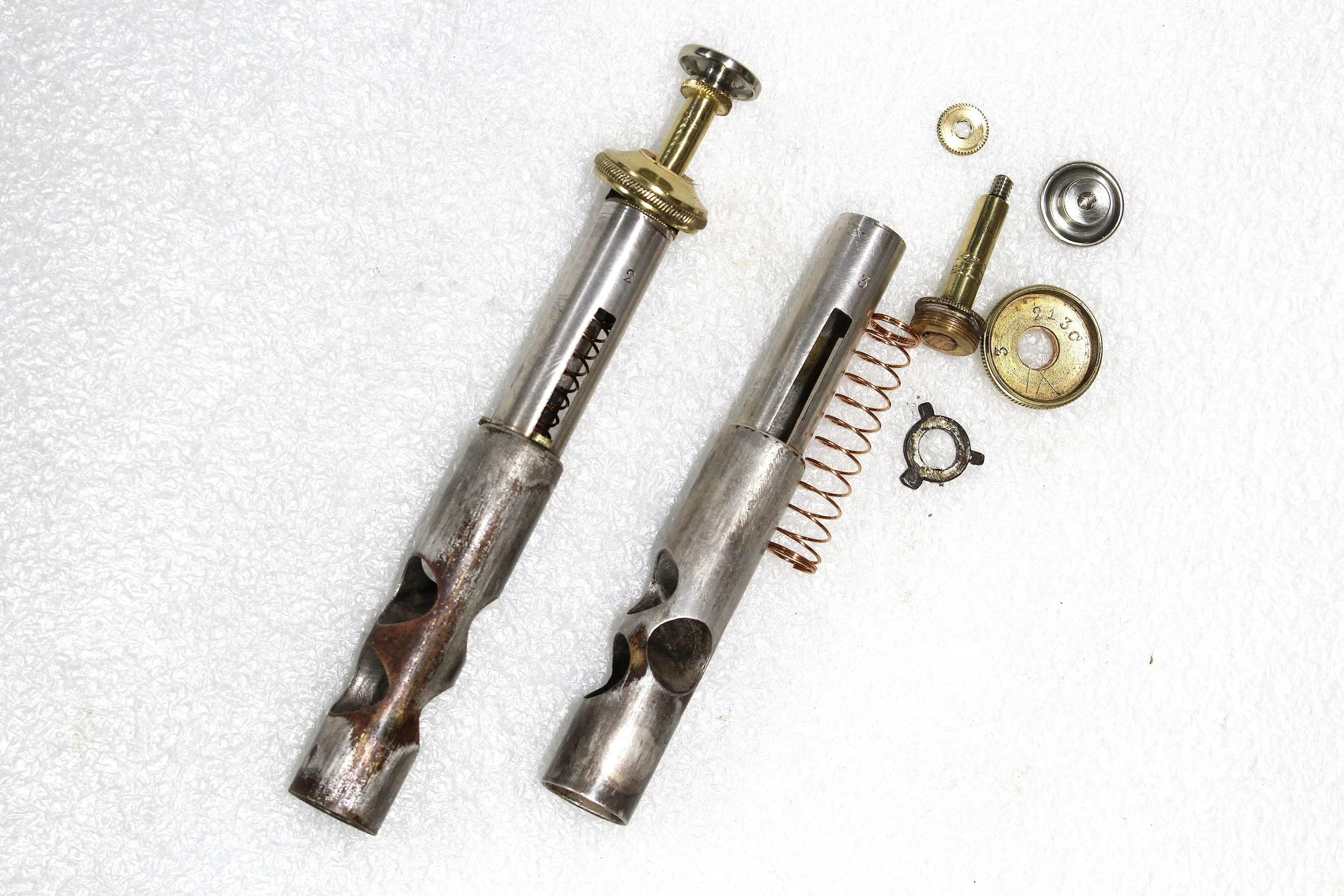

It is also possible that Distin was importing cornets from Antoine Courtois’ cousin, Auguste Courtois who was making brass instruments at 54 rue des Vieux-Augustins in Paris. Auguste was less focused on the foreign market, and judging by surviving instruments, with a much smaller production than Antoine. Some of his later products were based on Antoine’s designs. Auguste was creative, however, and produced some unique designs, including several different versions of his “cornet coulisse” (slide cornet), in which the tuning slide was long enough to lower the pitch by several semi-tones. The original concept needed no crooks for lower keys (presumably with longer alternate slides. In two examples that are known, the slide pulls to lower the pitch by one and two semitones, and they came equipped with Bb shank and G crook, which in combination with the slide, can be tuned by half steps down to F. More importantly, he was granted a 15 year patent for a new valve guide in 1847, comprised of a round plate with two rectangular lugs extending from opposite sides. These registered in shallow slots on the top of the casings and the piston was guided by slots in a tube mounted on top of the pistons (modern term: “spring barrel”) as they were depressed. The springs extend between these plates and the enlarged base of the valve stems. An amendment to the patent the next year specified one lug on each of these plates. Variations of this idea were very soon utilized by other Parisian makers and today, almost all cornets and trumpets use valve guides that are identical in concept to Auguste Courtois’ original two lug design. In 1851, Antoine Courtois was awarded a 15-year patent for another modification of this design that included three equally spaced lugs on each of the guide plates. This design was continued into the 20th century and copied by many other manufacturers including the Boston Musical Instrument Manufactory, starting in the early 1880s, and C. G. Conn, a few years later, which soon became the largest musical instrument maker. Surprisingly, Antoine Courtois produced some cornets in 1859 and 1860 with a different valve guide mechanism. It was a bit of a throwback to a design that had been used by English makers such as Charles and Frederick Pace in the 1830s and 1840s and German copies of those. As seen in the photo below, it involved a cylinder with a base plate attached on which the spring set and had a rectangular slot which slid along corresponding rails attached to the stems.

According to The Langwill Index, flute maker John Pask and German born Gotlob August Hermann Koenig, the leading cornet soloist in Britain, formed a partnership in about 1849 which involved importing musical instruments for sale from their shop in London at Lowther Arcade and Strand. These included Périnet valve cornets made by Gustave Besson, Antoine Courtois and other Parisian makers (likely including Gautrot), but also the earlier style cornets with Stölzel valves. Most of the cornets in collections today that were sold by this partnership are marked “Pask & Koenig” along with their address. Several of these are identifiable as being made by Besson. Only three Courtois cornets sold in London are known from this period and are engraved on the bells above Courtois’ stamped name and address: “PROVED / By / Herr Koenig / J. PASK / 8 Lowther Arcade / Strand London”. They all have Stölzel valves, in the form that is typically called “cornopean”. An engraved image of Koenig from the period clearly shows him playing a cornet with Stölzel valves. None are known with Périnet valves, but it seems likely that they would have also sold them, but at a higher price. This partnership was dissolved by mutual consent on April 10, 1851, shortly before the opening of the Crystal Palace Great Exhibition, although there were brass and woodwind instruments exhibited there under the name “Koenig and Pask”.

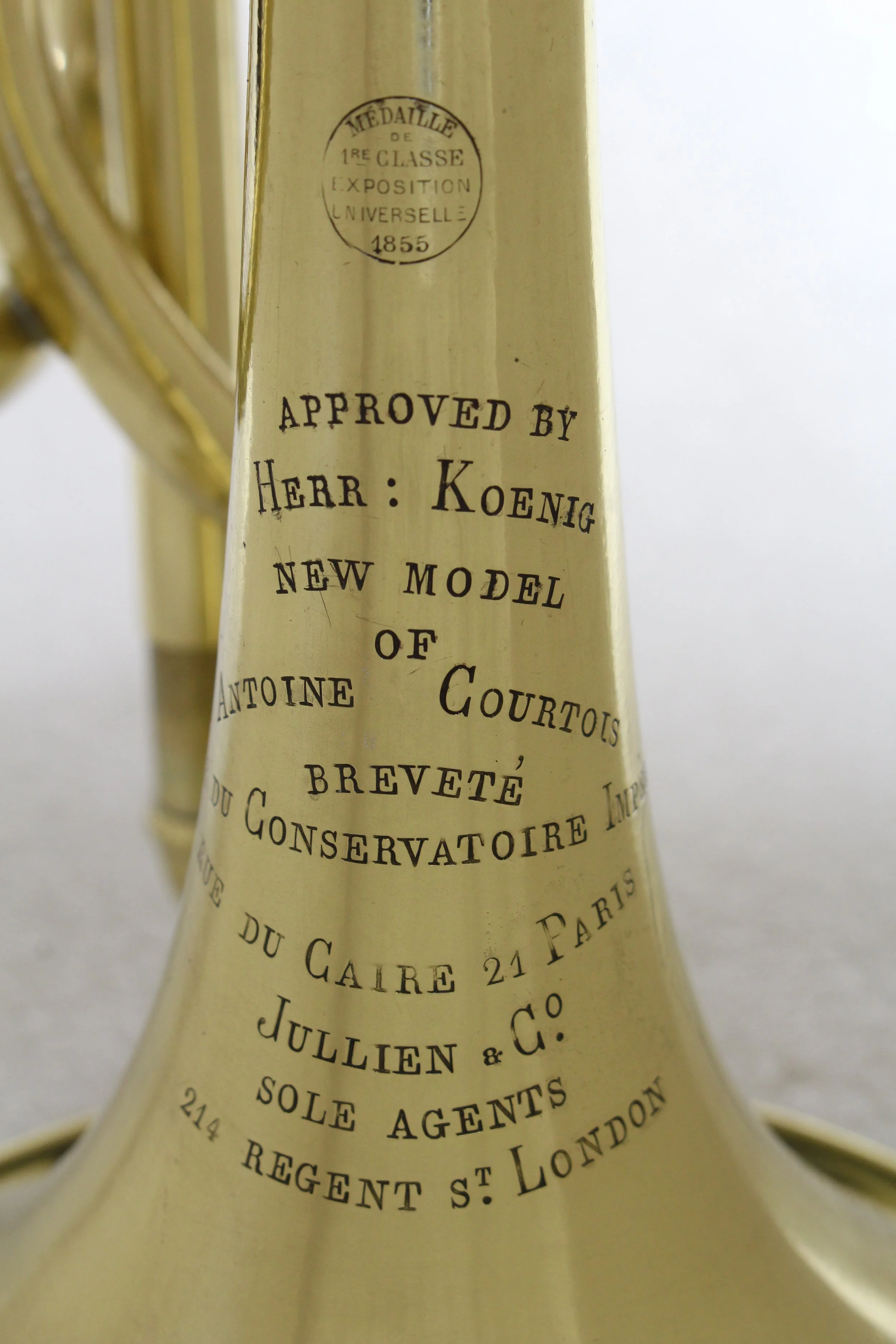

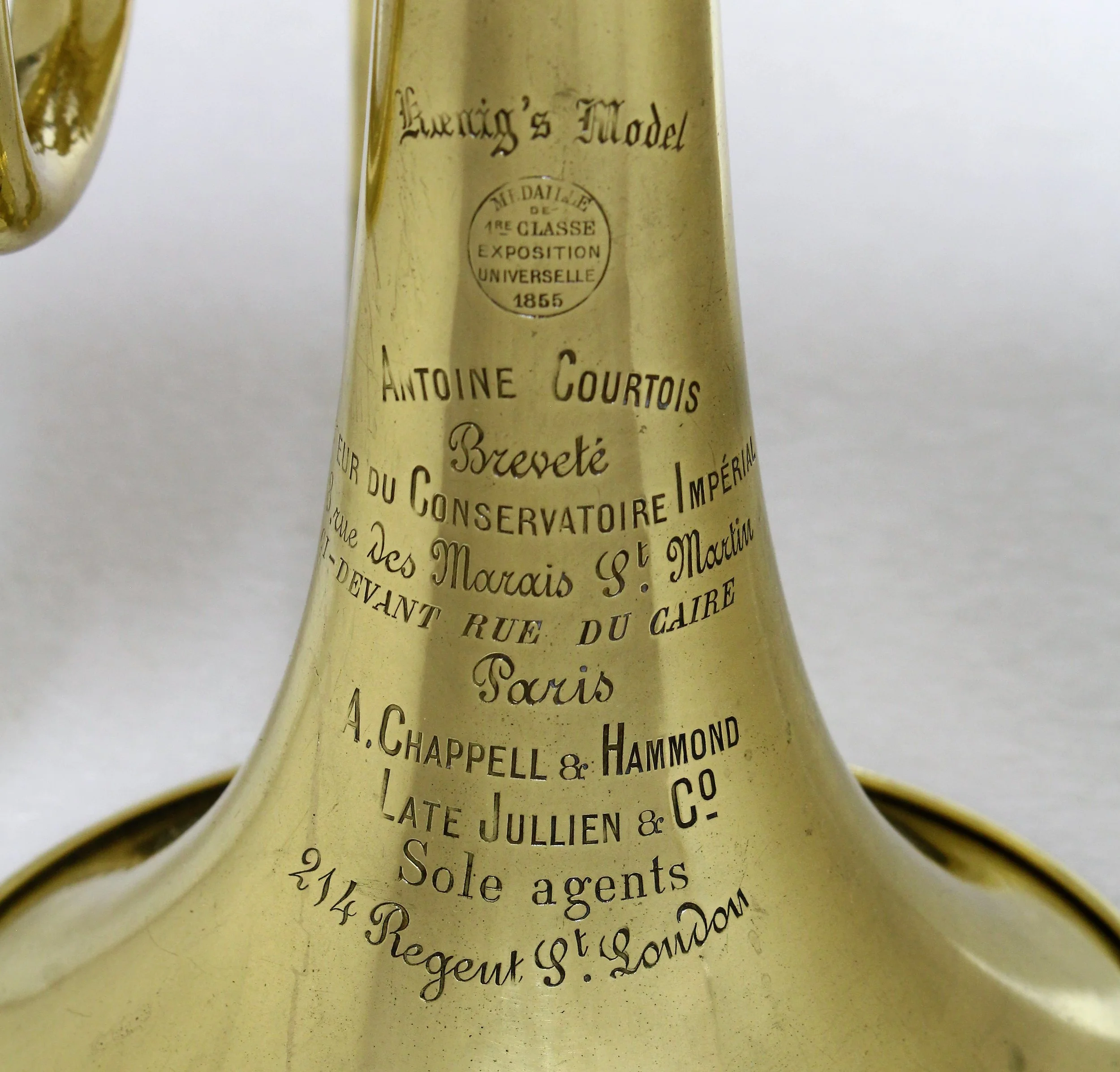

In November 1851, the famous orchestra leader, Louis-Antoine Jullien advertised in the London papers that he had purchased some of the instruments that were exhibited at the Crystal Palace, including those by Courtois and Besson and became the sole importer of these makes at his address, 214 Regent Street. The timing was good, and he gained the endorsement of Hermann Koenig. The earliest extant cornet sold by Jullien is also with Stölzel valves and engraved in a similar manner to those that had been sold by Pask: “Approved / by / HERR KOENIG” above Courtois’ stamped signature and “JULLIEN & CO. / Sole Agents / 214 Regent St.” below.

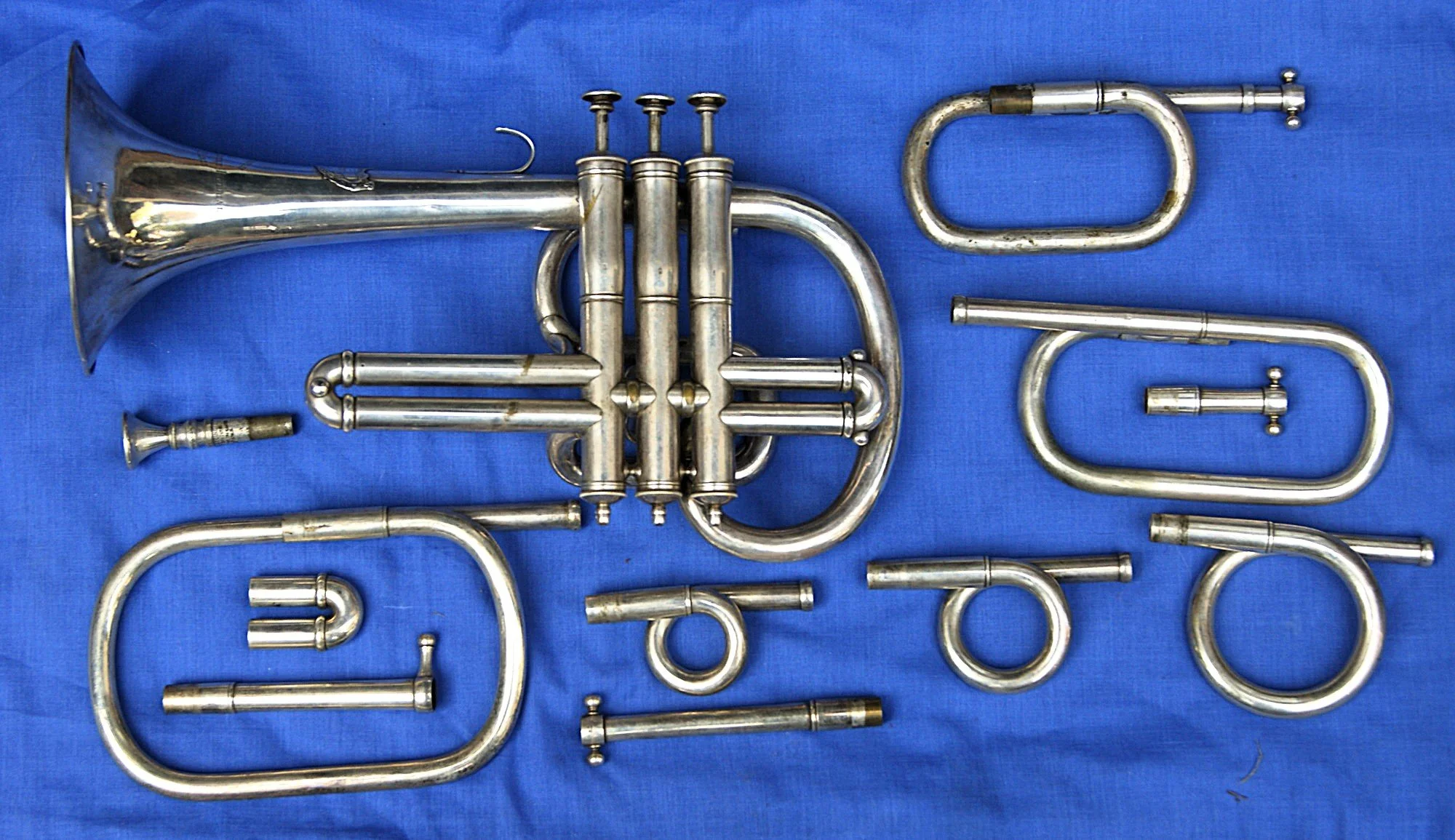

Courtois’ cornets were also available with Périnet valves and a third style that combined the two valve designs, with one Périnet valve between two Stölzel valves. Today, we refer to this design as “hybrid model”. Following another trend among French makers, Courtois also offered cornets with rotary valves, the two extant examples were also sold new in London. None of these cornet designs were unique to Courtois, other than his patented valve guides, and were sold by all the Parisian makers. The unique success of Courtois cornets may have been a result of a superior acoustical design, Jullien’s marketing budget, or perhaps a combination of the two factors.

Early in 1852 a new “Herr Koenig’s New Drawing Room Model” was introduced in newspaper advertising by Jullien in London, which was in the key of C to be played reading along with piano music. The Bb equivalent was then called “Herr Koenig’s Concert Room Model. Those model names were not marked on the instruments, but this was about the time that Courtois began stamping cornets that he sent to London: “APPROVED BY / HERR KOENIG”, in place of the engraved designation, that was likely applied in London. This endeavor was very successful as indicated by a survey of extant cornets made between 1855 and 1862, of which 76% were sold new in London.

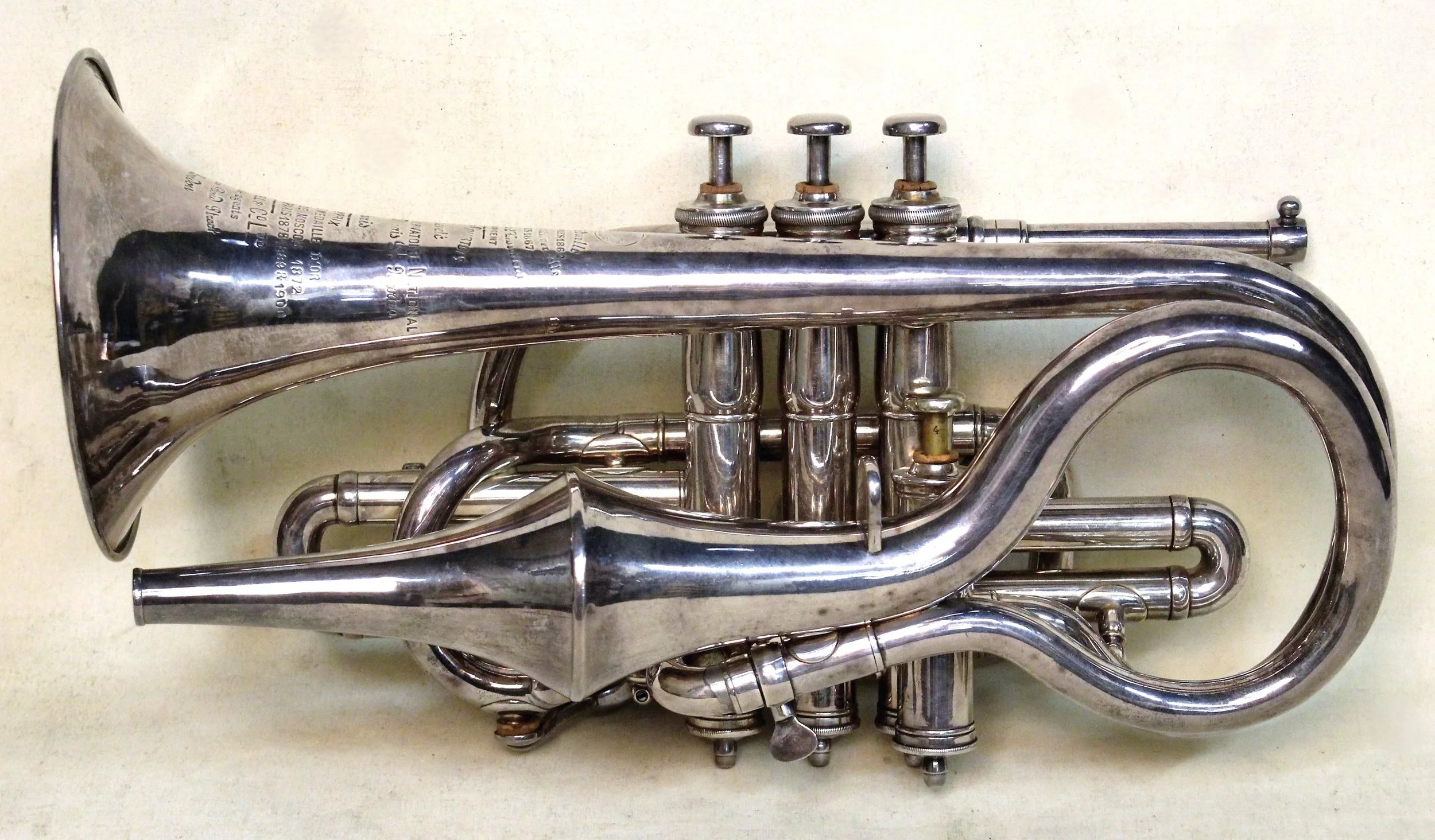

In about 1854 Antoine Courtois started making cornets with the bells on the left side of the valves, from the player’s perspective, although continuing the earlier style as well. This was an innovation; almost all cornets had previously been made with both the bell and mouthpipe on the right side. From the first brass instruments with valves, the mechanism was attached to to the “natural” instrument, without more modification than was necessary for the attachment. But cornets quickly became a new breed, with the valve being essential to its character, so no surprise that they would be more integral physically as well. Those sold in Paris were stamped “NOUVEAU MODÉLE / DE” above Courtois’ name and those by Jullien in London “APPROVED BY / HERR KOENIG / NEW MODEL / OF”. The two earliest extant, made in about 1855 and 1856 are the two earliest of what came to be known as “Modèle Anglaise” or “English Model” (Périnet valve cornet with bell on left side of valves) by any maker. They both have the double water key that is almost inseparable from this design, although isn’t mentioned in advertising until 1859. These two cornets also have a new variation of the original Périnet valves with rearranged ports that accommodated the bell being on the opposite side as well as reducing constrictions within the first and third pistons. Courtois must have taken inspiration from a new valve design, used by Besson, invented in 1852 by Charles Edme Rödel, with the goal of removing restrictions in the piston ports. Besson went on to patent two more arrangements of the ports in 1854 and 1855, with the same goal. In Courtois’ new design, the second piston retained the original Périnet design with ports in which the bores are more restricted. Jullien was no longer selling Besson instruments in 1854 and none are known with Koenig’s endorsement marked on them after 1851.

Courtois made English model cornets with the earlier valve designs as well, seen in at least two examples of the “hybrid” design. None are known with three old style Périnet or Stölzel valves, although two of the former exist with removable bell that angles upward at about a 40 degree angle that would most conveniently be placed on the left side. These pre-date the New Model and might have been a factor in the new design idea. The older styles were losing favor by then and were likely relegated to less expensive cornets. Courtois concentrated on making English style cornets with new model valves; older French models made after 1862 are exceedingly rare. Even the Paris Conservatoire awarded English model cornets to the winner of the solo competition. “Modèle Française” cornets stamped “NOUVEAU MODÉLE / DE” above the name had the “New Model” valve design, but with the first valve tubing “mirror image” of the Modèles Anglaise to accommodate the bell mounted on the right side. This indicates that having the bell on the left shouldn’t be thought of as the defining characteristic of the New Models, but rather, it is the valve port design. Presumably, the Modèles Française were made available for the more conservative French cornetists and the military.

A short time after Koenig’s death in late 1857, the Bb variation of the new model sold in London were all stamped “Koenig’s Model”. At about that time, “Nouveau Modèle” was dropped from the stamping on the cornets sold in France. They were available from Jullien & Co. for £9 9s “with improved water-key” and £8 8s “with waterslide”. They were also available in “the New Metal Imitation of Gold” (presumably made of gold brass, with higher copper content) for £13 13s, “Solid Silver” for £40, and the same with gold (plated?) mountings for £50. Two examples of solid silver cornets are known to survive today including one that was presented to a British Army musician in 1861, the other made in about 1868, is without any presentation indicated, but exhibits all the Riche decoration described below. No extant cornets are known made of the “New Metal Imitation of Gold”, but two examples exist in solid nickel silver (German Silver) from later decades, an option that doesn’t appear in advertising.

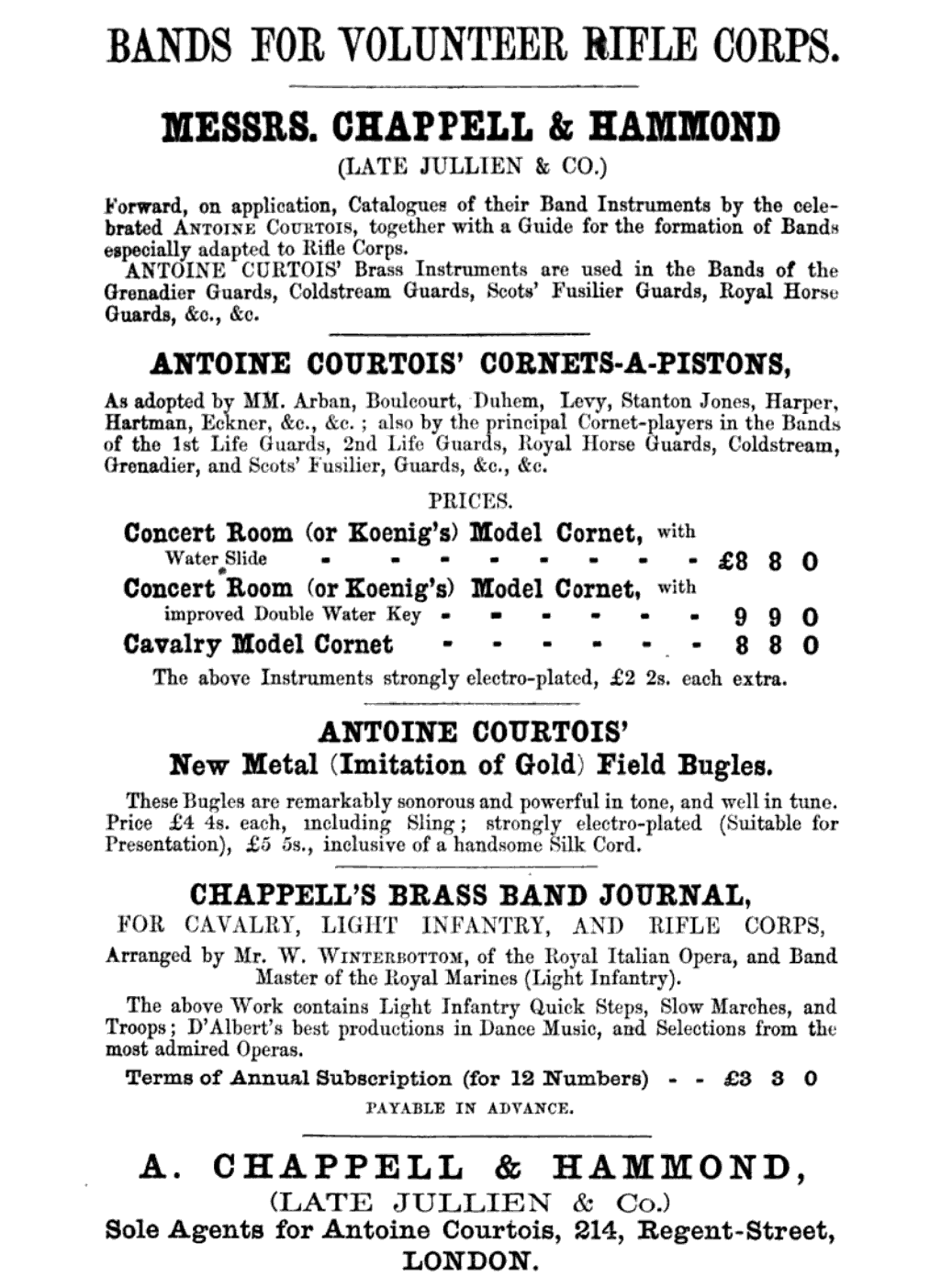

Jullien was first and foremost a promoter and his advertisements might have been confusing or even deceiving. In March 1852, touting a large consignment of Besson and Courtois cornets, £8 8s, first quality and £6 6s second quality. While it is possible that Besson and/or Courtois were producing less expensive instruments, perhaps with the old-fashioned Stölzel valves, those by Courtois were still being played by Koenig and the second quality cornets may have been made by another maker. Several years later, in ads headed by the statement “Manufactured by Antoine Courtois”, he listed second quality cornets, presumably with Stoelzel valves, for as low as £2 2s. Perhaps this met with negative responses and later versions of this ad stated that the lower priced cornets were “examined by Courtois” (more correctly by Courtois’ agent in London). Various other names were given to lower priced cornets: “Military or Cavalry Model” for £6 6s, “Amateur” for £5 5s and “Navy” for £4 4s. Finally, in 1859, Jullien listed “Antoine Courtois’ Besson Model Cornet” for £6 6s. No information has been found to show that these lower priced Courtois cornets were older models or that Jullien might have been selling those of other makers, claiming to be by Courtois. No longer selling Besson instruments, Jullien may have intended to communicate his view that Besson cornets were of lesser value, and if he failed to keep them in stock, might sell more of the full priced items. When A. Chappell & Hammond took over the London franchise about a year later, they simplified this a bit, listing “Concert Room (or Koenig’s) Model Cornet, with Water Slide” for £8 8s, “Concert Room (or Koenig’s) Model Cornet, with improved Double Water Key” for £9 9s, and “Cavalry Model Cornet” for £8 8s. Only two cornets are known with “A. Chappell & Hammond” indicated on the bells, both Koenig’s Models, one each of the water key and water slide variants. The specifications of “Cavalry Model” and earlier lower priced cornets by Courtois are otherwise unknown. Regarding the Besson model mentioned, it is interesting to note that in later years, Courtois made copies of Besson cornets. This included French model copies of Besson’s Etoile in the 1870s and even more numerous examples exist made in the 1880s and later, when Besson was selling many more instruments than Courtois. There is no reason to believe that these are lesser in quality than Courtois’ more popular products.

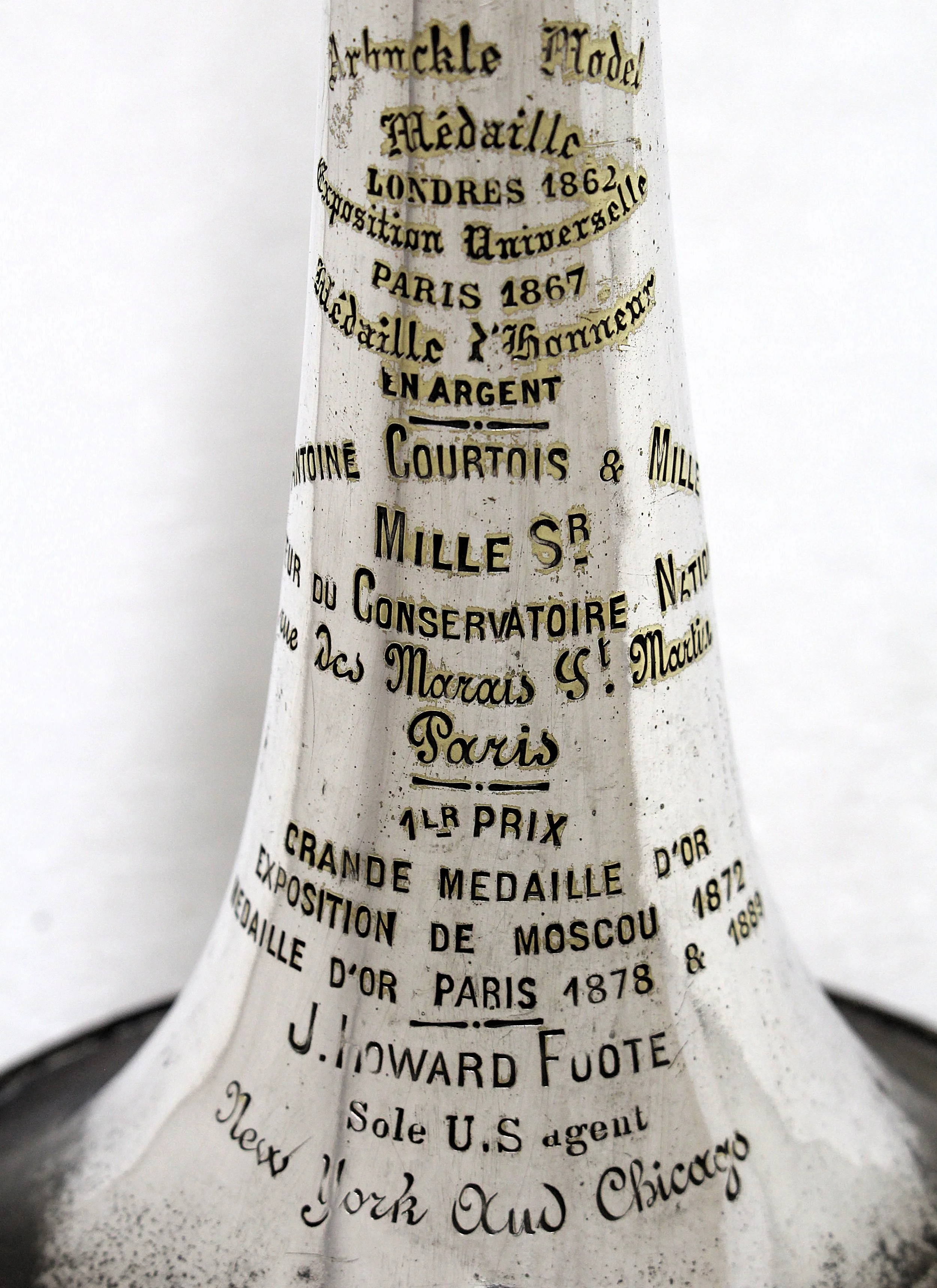

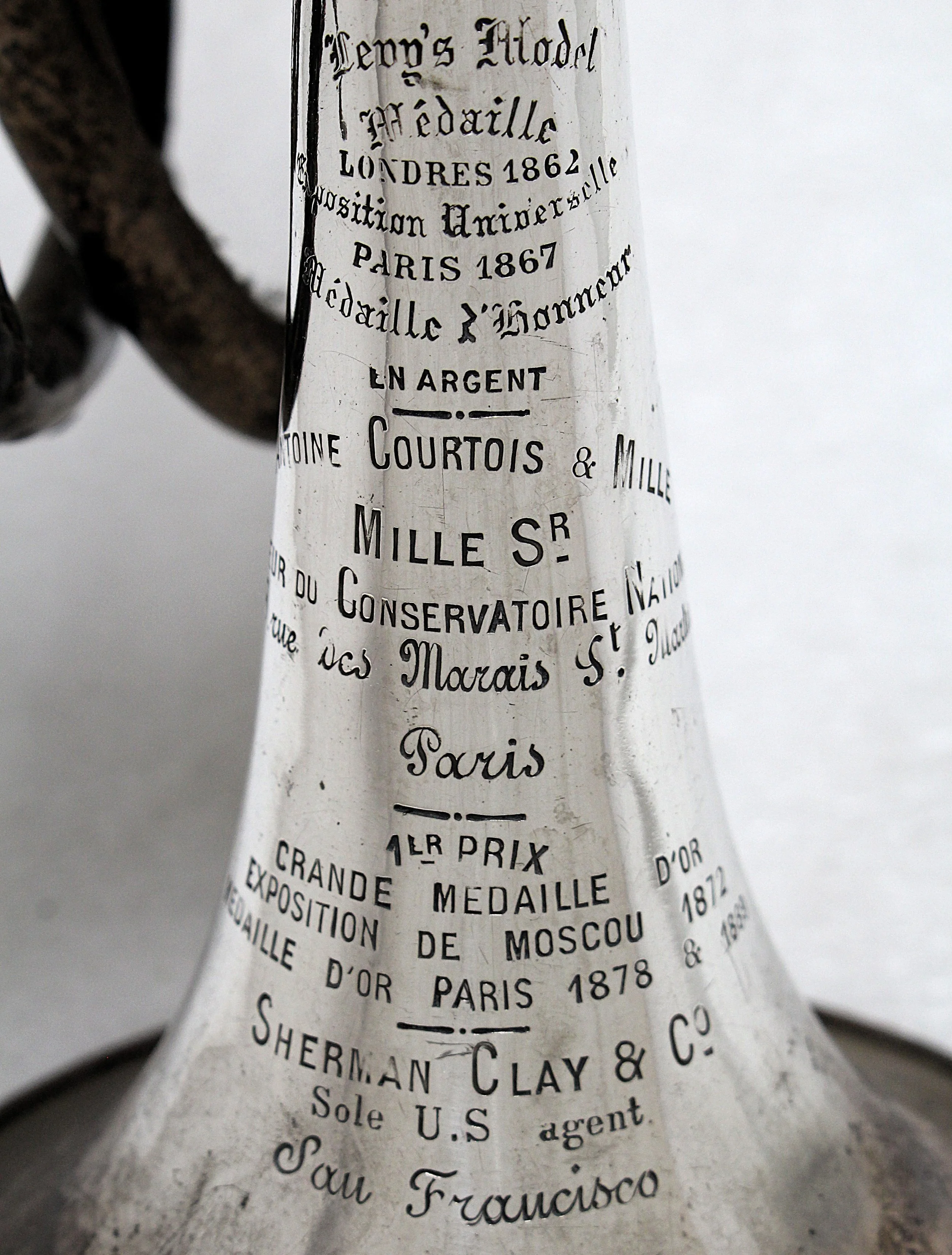

(Jean-Baptiste) Arban was first mentioned as playing a Courtois cornet in advertising by Jullien and Co. in 1854. Advertising didn’t mention a distinct Arban Model until later and the model name was not marked on the bell. The earliest indication of an Arban Model was in J. Howard Foote’s catalog of about 1885 and it was also called the “Reynolds Model”. The first mention of Jules Levy playing one is by Chappell & Hammond in 1860 and in October of 1864, The Musical World reported that he was playing “on the new cornet, made expressly for him by Antoine Courtois.” This was right after Levy’s first performances outside Britain that included soloing in Paris. It was likely the origin of “Levy’s Model”, the earliest known example with the name stamped on the bell was made about that year. The earliest known Arbuckle model was made about 1877, and the first Emerson model was 1881.

The earliest New Models with double water key have a wider third valve slide crook that was later an identifier of the “Arban Model” and “Reynolds Model” (J.H. Foote catalog). However, some later Koenig’s and Levy’s Models have the wide third valve slide No explanation of the variations beyond the earlier Koenig’s water slide model are known from the sources in the first thirty years or so. In later literature, such as Foote’s catalog of 1885, Levy’s Model is described as “small bore” and the others “medium bore”. Only the Emerson Model that was “large bore". A letter written in 1880 was published by Foote in that catalog in which Arbuckle mentions his preference for the medium bore. Careful measurements of the valve bores in a sample of 72 cornets, including (presumed) Arban, Levy, Arbuckle, three Emerson models and others with no model designated, shows a relatively high variation in measurements. Levy’s Models ranged from .449” to .464”(11.4mm to 11.8mm), averaging.453”(11.5mm). Koenig’s Models ranged from .447” to .465” (11.35mm to 11.8mm), averaging .459”(11.66mm). Arbuckle Models ranged from .449” to .461”(11.4mm to 11.7m), averaging .457”(11.6mm). Arban models ranged from .453” to .469”(11.5mm to 11.9mm), averaging .460”(11.7mm). The Emerson models are .473” and .474”(12mm). 16 other cornets without model designation ranged from .453” to .464” (11.5mm to 11.8mm), averaging .458.3” (11.63mm).

The next thought might be that the models may be distinguished by a difference in bell sizes. Accurately measuring bells is even more difficult than measuring cylindrical tubing, which is already fraught from damage, age, repair and the crust that often covers the interior of old brass instruments. However, Dr. Arnold Myers has developed an accurate method of measuring bells and has shared his measurements of 12 Courtois cornet bells and 5 more were measured by Robb Stewart using his technique. This sample includes one example pre-dating the “New Model”, three “New Models”, three without model names indicated, four Koenig’s Models, two Arbuckle Models, and one each of Levy, Arban and Emerson Models. All these bells are remarkably close in dimensions. The largest variation is in the last 2 ½”(6.35cm) of the flares (the Emerson appearing largest here). Not only is the flare the most difficult to measure precisely but is often stretched from its original profile by major damage, but also unskilled removal of minor dents. The 17 bells, ranging in dates of production from 1852 to 1892 may have all been made on the same mandrel, or at least adhering closely to the measurements of the successful design. The possible exception may be the Emerson Model that appears slightly larger in the flare, especially the last 1 3/8” (35cm), although without more of that model measured, we can’t conclude that it was intended to be larger there. The bores of the main tuning slides follow a common pattern, with the upper slide tube (lower tube in the case of those with water slides) being the same measurement as the valve slides and the other tube (closest to the mouthpipe along the length), slightly smaller. The exceptions are some of Courtois’ earliest cornets in which the bore of both the main tuning slide tubes are the same as those of the valve slides. A smaller sample of mouthpipe tubes have been measured. Unfortunately, most mouthpipe shanks have been lost or damaged, but the few measured indicate little variation. Comparing the starting (smallest) diameter of the fixed portion of the mouthpipes in a population of 9 cornets, shows a larger variation, from .395”(10mm) (mid-1860s Koenig’s Model) to .410”(10.4m) (Arban Model, 1875 and Arbuckle Model about 1892), .405”(10.3m) being both the average and median. More study would need to be done to understand better the design intention of these.

Courtois valve button design changed over the years, following design trends of other makers. The earliest had the male threads on the stems and a thin knurled nut between the stem and button. The purpose of the nut was to provide a wide surface to to tighten against, lessening the likelihood of splitting ivory buttons, but the same design was used for brass and nickel silver buttons as well. In 1856, the design was changed, with the male threads on the button, eliminating the nut and reducing the height. The next change, in about 1862, was to make it more cup shaped, but retaining the same diameter, .59 inches (15mm). In about 1872, the outside diameter was increased to .635 inches, (16.13mm) and slightly deeper. They were made deeper yet in the late 1880s. The large, cup shaped buttons with mother of pearl inserts were available from about 1873.

Courtois was also making soprano cornets in Eb early on, although only 11 are known to survive, along with three in F. With such a small sample, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions. The earliest known extant was made in late 1854 or early 1855. This example used the original Périnet valve design, although with his patented three-tab valve guides. It was supplied with shanks and crooks to tune down to G. His next model was presumably available shortly after the introduction of the “New Model” Bb cornets in about 1855, although the earliest known is from about 1867. It was shaped much like a Bb cornet in miniature, with the mouthpipe and tuning slide assembly similar to the “waterslide” model, although without a waterslide. It had shanks for Eb and D and a crook for C. By the early 1870s another model was offered along with the previous one, using valves of the same bore, bore size (.4” or 10.2mm) but shorter, necessitating the the use of simpler, fixed guide, in place of those with three tabs. It was longer overall, with a larger bell flare and tuning with an integral sliding shank. J. Howard Foote’s catalog from 1885 offered both and called the long design “NEW MODEL” and stated that they were equipped with a crook for D, although none are known with that accessory. The short design was called “SOLO MODEL” and continued to be listed in the catalogs until after 1901, while the “NEW MODEL” was no longer shown in Foote’s catalog of 1897. Two of the sopranos in F were made in the mid-1870s and are of a completely different design, without Coutois’ valve guides, but guided with screws through the lower valve casings that register in a slot in the piston. This is an older design that is only seen in Courtois’ trumpets until about 1877, which begs the question that they are not cornets, but intended as soprano trumpets. They are short models with relatively large bells and removeable mouthpipe tuning shanks. The third of these (formerly in the Holton-Leblanc collection in Kenosha, Wisconsin, although current location is unknown), was made after 1880, when Mille became a partner. It has no visible valve guides in the casings, so presumably has guides fixed to the pistons, like the “NEW MODEL” soprano.

Cornets by Courtois in the key of C were available from at least 1852 as mentioned above, although never approached the popularity of those in Bb. In the early examples, they were supplied with crooks for pitches to F, but by the 1890s, only to A.

The three catalogs mentioned above also illustrate an echo cornet, the earliest extant having been made in about 1874. Only 6 examples are known, the latest was made about 1900.

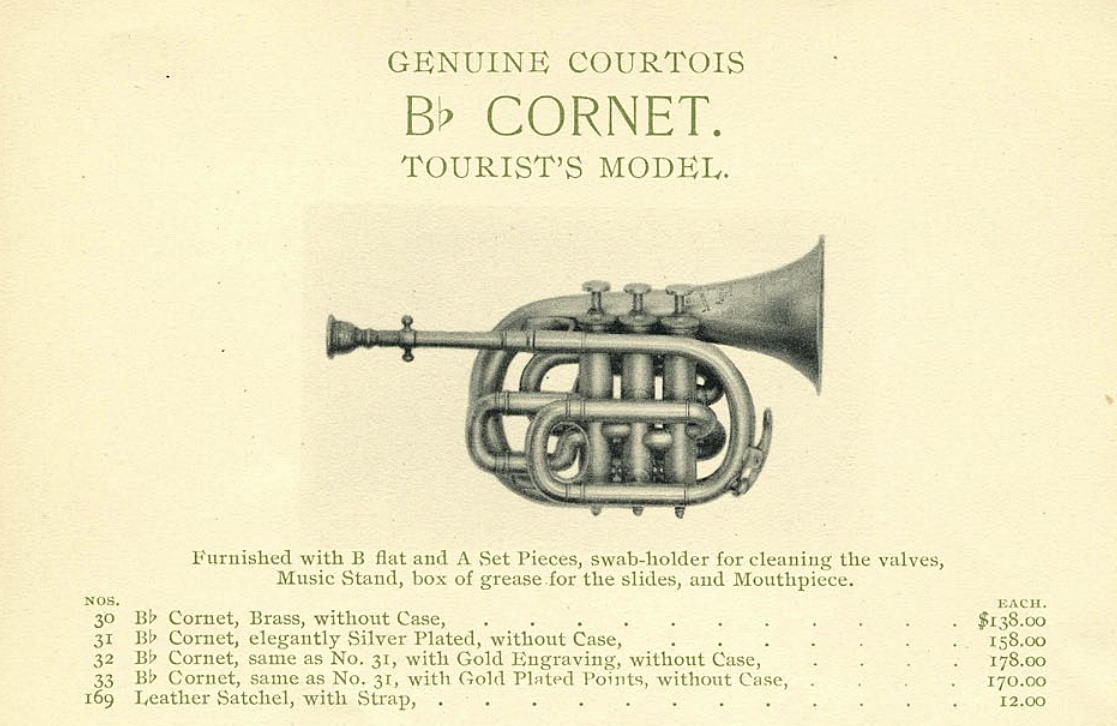

Even more rare is the “TOURIST’S MODEL” with only two known. This is a compact Bb “pocket cornet”. The earliest of these known was also made in about 1874. They were listed in both Foote’s 1885 and 1897 catalog, but no longer after 1900. Possibly related to this is the pocket cornets in Bb that were listed in Boston Musical Instrument Manufactory’s catalogs in the 1880s and 1890s. The engraved image appears the same design as Courtois’ and the 1890 Boston catalog calls it the “Tourist”. Without any known examples to examine, we can’t know if these were made in Paris and resold by Boston or just a close copy of Courtois’. The Courtois was listed for $10 more at $65 for brass and $75 for silver, but Foote’s 1897 catalog (presumably after Boston discontinued offering the model), more than doubled the prices to $138 and $158 for brass and silver respectively. Boston continued to offer pocket model variants of both piston and rotary valve Eb cornets and the solo alto horns into the 20th century, but not any in Bb. Many of the pocket model Eb cornets and at least three of the altos exist in collections today, although no Boston Bb pocket model cornets are known to survive.

At some point, likely in the 1860s or 1870s, Courtois also started making artist model mouthpieces along with his “Courtois Model”. These included Arban, Levy, Arbuckle, Reynolds and lastly Emerson models. In the case of the Arban mouthpieces, they were subdivided into seven sizes from 1 to 7, the latter being the largest. In their 1920 catalog, the interior diameters were given to be from 16mm to 19mm. Just three originals were available for measuring, numbers 2, 3, and 7, all made some time between about 1870 and 1900, to compare against the sizes stated in 1920. Measuring where we are accustomed to today, they are about 1mm smaller. That is, measuring from a point where the radius of the rim transitions to the radius of the cup, which is roughly the diameter of the area of the player's lip that vibrates. The catalog measurements would agree if one were to measure from points at about 1/5th the width of the rim. The other artist models were mostly single sizes, presumably modeled after what the musician used. While it doesn’t seem likely that Arban would have played on all the sizes of his model, it is reasonable to assume that the intention was to make the choices available suiting the needs of students while he was professor of cornet at the Conservatoire and perhaps earlier while he taught at the l’École Militaire as well as for the cornet playing public. Since most instruments don’t survive with the mouthpiece(s) that were supplied with them when new, it is much more difficult to assign a manufacturing date to them. Courtois mouthpieces can be differentiated once Mille’s name was included in the name stamp in 1880. Before that, the word “BREVETE” appears under the name and after 1900, neither “MILLE” nor “BREVETE” is included. Markings and design changes in the earlier years are not known currently. Most include the address rue des Marais and none are known with the previous address on rue du Caire. That isn’t surprising, because the practice of marking mouthpieces didn’t become common until some time around 1870.

By 1853, Courtois was producing a complete line of brass instruments with Périnet valves from Eb soprano cornet to Eb contrabass tuba, trumpets, horns and alto, tenor and bass slide trombones. The larger production necessitated hiring more employees and in 1856 moved from rue du Caire to larger quarters at 88 rue des Marais, St. Martin. An important component of the industrial revolution was power from water or steam and there was no waterpower within the center of Paris. Any lathes and drilling machines in the Courtois shop would have been human powered, either by the operator with a foot treadle or a second man turning a large flywheel. Steam engines had been around for a century before Antoine Courtois’ uncle and father moved to 21 rue du Caire but were only for pumping water (sometimes to turn a waterwheel with which the speed and torque could easily be controlled) and of no use in small industrial shops. Only after improvements in efficiency and utility during the first half of the 19th century did steam become a useful and economical source of power for turning shafts to power machines. The most important advances happened in 1849 and 1862, but no evidence has been found that the building on rue des Marais already had steam power or when it might have been available. No evidence has been found to determine when or if the shop ever had steam power, but not having it in the late 19th century would have been a handicap in competing with more mechanized shops. The company was at that address for about 30 years after electric motors were available to power small industrial shops, when they moved to rue de Nancy in 1927.

Shortly after the 1856 expansion, Courtois contracted with music publisher A. Büttner as sales agents for St. Petersburg, although no instruments are known that indicate being sold there. He continued entering instruments in international exhibitions, winning prize medals in Paris 1855, 1867, 1878 and 1889, London 1862 and 1885, Moscow 1872, Boston 1883 and others.

In about 1854 Courtois introduced the “Koenig-Horn”, a circular bodied alto with bell downwards, nominally pitched in F with crooks for Eb, D and C. The taper and flare of the bell was like a small alto (tenor) horn or modern flugelhorn. Hermann Koenig was well known for his expressive ballad style of playing and this instrument would have worked well for the alto or high tenor range. The earliest known example had engraved on a silver shield “à son ami / Herman Koenig” and lacks Jullien’s stamp indicating that it went directly from Courtois to Koenig, rather than being handled by Jullien. Other circular horn ideas came later in the century with the Antoniophone and Melody Horn. The Antoniophone was a family of instruments, with the tubing in sort of a “figure 8” shape, from Eb soprano (cornet proportions) to Eb bass. The Melody Horns had circular bodies, with bells upright in F alto with slide extension for Eb and in C tenor with slide extension for Bb. The proportions and sound quality of the Melody Horns approached that of actual horns. None of these instruments were made in large numbers and survivors are very rare.

Despite the appearance of success, Jullien may have spent too much on promotion of both his orchestra and retail business resulting in bankruptcy, his second, in late 1857. The death of Hermann Koenig may have added to this trouble because he had interest and perhaps investment in the publishing side of the business as well. Jullien was able to continue in business, but only until early in 1859, when he left for Paris in May. The exclusive importation of Courtois instruments was taken over by A. Chappell & Hammond at the same address on Regent Street shortly after. Alfred W. Hammond had worked in the publishing arm of Jullien & Co. and had previously run his own music publishing business at 9 New Bond Street. The partnership was then succeeded by S. Arthur Chappell by October of 1861. Samuel Arthur Chappell had also worked for Jullien & Co. during the 1850s and travelled with him on his American tour in 1854 and 1855 that was sponsored by Chappell & Co.

S. A. Chappell was the son of Samuel Chappell who had founded Chappell & Co. in 1808. He was in an excellent position to take advantage of the boom in demand for pianos and music for piano in the homes of the growing middle class. After Samuel’s death in 1834, his widow Emily headed the business, first with the help of her oldest son, William, and then her son Thomas Patey Chappell. She retired in the 1860s but continued to live in a large house on the premises of the business. They were publishers, concert agents and piano manufacturers at 49 to 52 New Bond Street. Chappell & Co. had published some of Jullien’s music in the 1840s and advertised Courtois cornets available for sale during the 1850s, presumably acquired from Jullien & Co. When Chappell & Co. incorporated as a limited liability company in 1896, S. A. Chappell was on the board of directors, but also maintained his business of importing Courtois instruments until his retirement in 1901, when he turned it over to the corporation. Chappell & Co. continued in the music business into the 1980s and the name still exists in Warner/Chappell Music, the publishing business having been purchased in 1987.

S. Arthur Chappell also imported Albert clarinets from France as well as having cornets made to be sold under his own name. The photos below show one of these on which the bell stamp advertises Courtois brass instruments and Albert clarinets. The S. Arthur Chappell brand cornets may have been made in England, but it is more likely that he contracted with a French maker to have them made to appear as close to Courtois cornets as possible and used valve assemblies purchased from the same pistonier (maker of valve assemblies) that supplied Courtois. While it is possible that Chappell contracted with Courtois to make these for him, it seems unlikely, especially if there were sold at prices less than the authentic Courtois cornets.

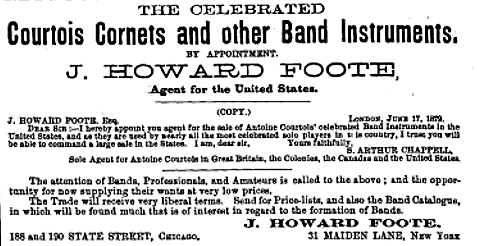

Chappell’s exclusivity also extended to the “Colonies, the Canadas and the United States”. He sold Courtois cornets through music dealers such as Edward Hopkins in New York and Henry Prince in Montreal. By the late 1870s, they had become very popular in the US and the sole right to sell them there was granted, in 1879, by Chappell to J. Howard Foote in New York and Chicago. The earliest of these were engraved with Foote’s name below Chappell’s stamp, but shortly after, the latter was eliminated, and they were sent from Courtois in Paris stamped with Foote’s name on the bell. Expanding to the western US, in about 1890 sole distribution was granted to Sherman Clay in San Francisco and again, sent from Courtois with bell stamp indicating as such.

From the early years, Antoine Courtois offered deluxe versions of his instruments, with engraved decoration and sometimes with stamped or cast shield or wreath applied to the bell and stamped embossed decoration on ferrules, brace and waterkey nipple flanges and valve caps. These included the instruments presented to the students of the Conservatoire Nationale de Paris as a prize for winning the solo contest for trombone and trumpet starting before 1840 with instruments made by Courtois Frères. The earliest of these known is a trombone presented to a student in 1838, that is not decorated beyond the engraved presentation. That trombone is in the collections of the Paris Museé de la Musique. By 1840, these had a wreath engraved or applied to the bell above Courtois’ information with the winner’s name engraved within and an engraved or cast garland or krantz applied to the bell rim and mother of pearl inlayed finger buttons. Before silver and gold plating became common in the 1860s, the decorative trim was often made of German silver or an alloy similar to Sterling silver. Decorative engraving could be ordered on an otherwise standard instrument as seen on one given by Patrick Gilmore to Matthew Arbuckle in 1876 and one given to Walter Emerson by his father in 1881. Courtois also offered the other decoration mentioned above at two levels, Demi-Riche and Riche. Demi-Riche had a silver shield intended for engraving, decorated with nudes, flowers, etc. applied above Courtois’ signature stamps, along with embossed decoration and decorative engraving around or below the bell stamps. Jules Levy’s favorite cornet features this option. The Riche instruments had a plain silver shield for engraved presentation, decorated ferrules, flanges and caps and more decorative engraving than on Riche. Also Courtois’ name, address, awards etc. were hand engraved in a decorative script rather than being stamped and valve buttons often featured mother of pearl inlay. The cornet presented to Howard Reynolds in 1875 that he played the rest of his life featured this option.

From about 1855 until after 1900, the valve assemblies exhibited the same design and construction that started with the New Model. This included the unique port design and three-tab valve guides as mentioned above. Another detail that is easily seen is two braces between the valve casings, below the ports, rather than four as seen in most other makes of piston valves. Also, the pistonier (valve maker) would scribe the valve parts (top and bottom caps, stems, piston assemblies at the top of the spring barrel, and casing assemblies inside the top of the ballusters) in a batch of valves with a sequence of Roman (or, rarely, Arabic) numerals, then Courtois would stamp Arabic numbers as well. The latter always started with “1”. For instance, the valve parts can be scribed “X, XI, and XII”, then stamped “1, 2, and 3” respectively. Courtois would also scribe lines on the top of the waterkey mount, perhaps to keep track of individual cornets as they are assembled, but not related to the valve scribe marks. I through V have been observed.

Close examination of these details along with measurements of the threaded parts: caps, stems and buttons show that assemblies from the same pistonier were used by at least ten other makers, mostly in the US. We don’t know who was importing these assemblies to the US, but it may have been J. Howard Foote, who had been involved in the importation of musical instruments and parts starting by 1857, when he went to work for J. A. Rohé in New York. This practice likely started after 1866, when Courtois’ patent protection of his valve guide design had expired, and being in the public domain, could be used by any maker. Ironically, some of these valve assemblies were used in some of Henry Distin’s cornets that he made in New York City in the 1880s. In Distin’s London factory, his valve port design was a unique combination of those by Courtois and Besson, as well as the pistons having a new single wall construction (Patent Light Valves) invented by Eugene Dupont for him in 1864. His cornets that were made in New York from 1878 to 1881 utilized valve assemblies purchased from several pistoniers using older technology, some with valve guides fixed to the pistons and others with the Courtois style valves. All these cornets are copies, to some degree, of the New Models by Courtois and very similar to the Distin cornets made in London. While it is possible that Courtois, like a few other makers, were selling valve assemblies to these smaller makers, it seems unlikely that they had enough excess production capacity. Rather, they were a somewhat specialized shop, whose products were more expensive than almost all other makers. That leads us to conclude that Courtois relied on an outside pistonier that had enough capacity to also supply these other smaller shops.

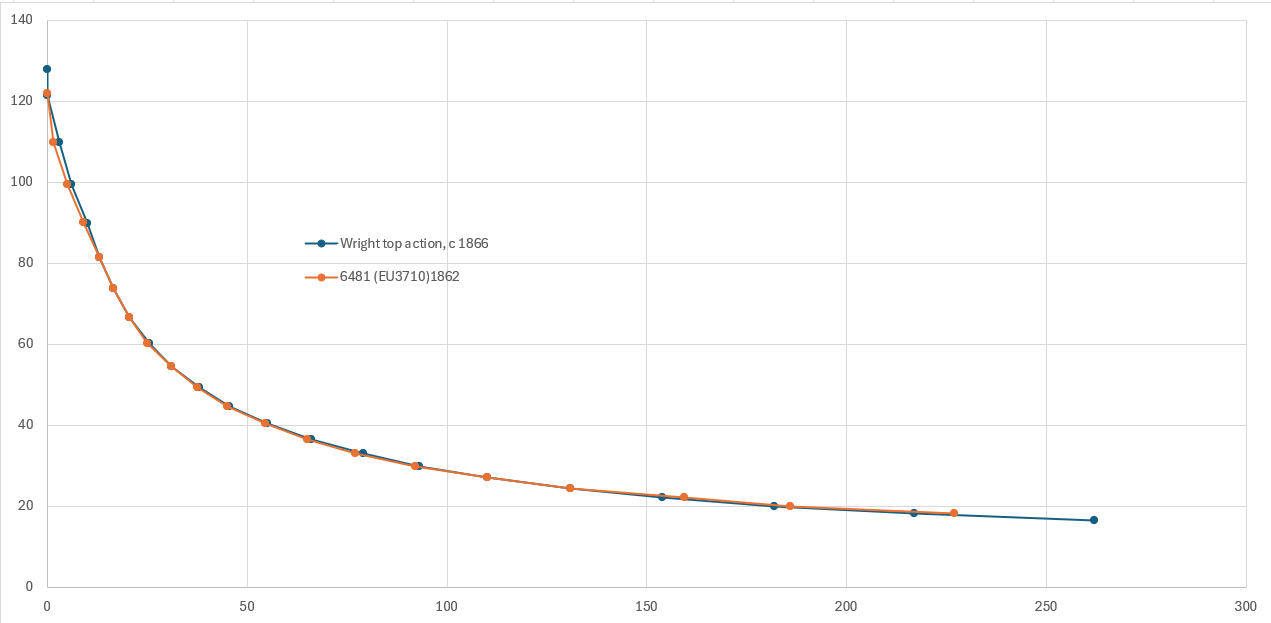

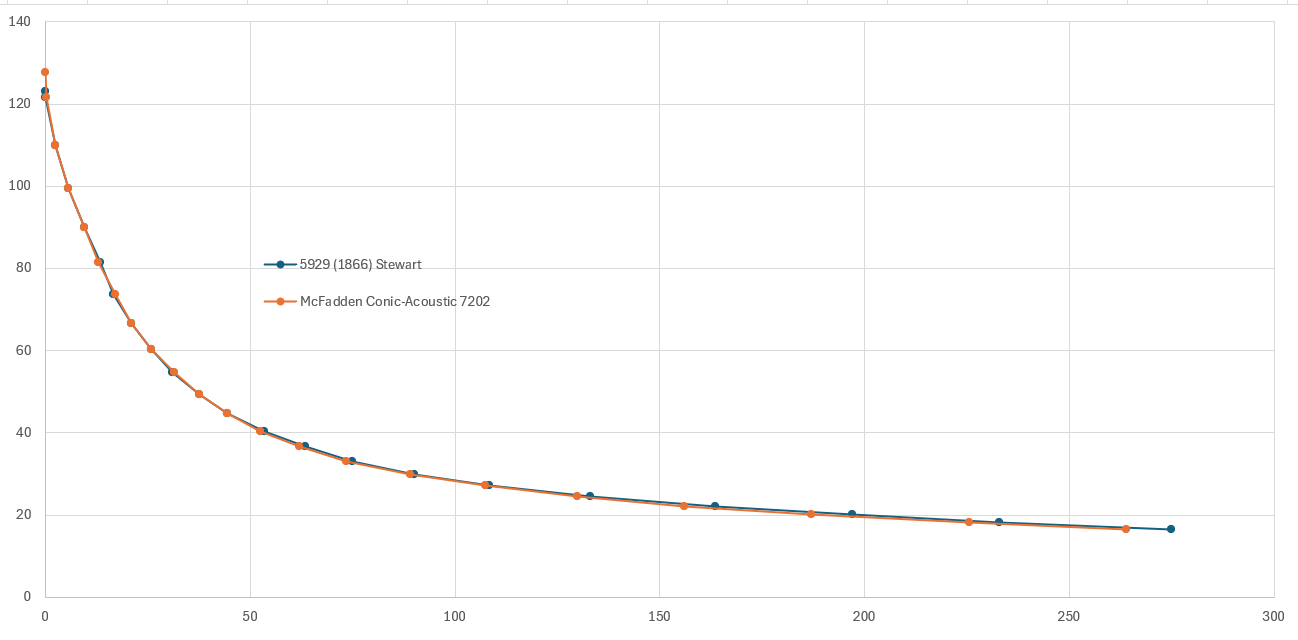

Besson was one of the very few brass instrument makers that did not make copies of Courtois cornets, and despite Courtois’ fame as the choice of the most famous soloists, they soon were selling many more instruments. Most other makers eventually made copies of cornets by both Courtois and Besson. As already stated, some of the Courtois copies were mostly cosmetic, without matching the dimensions very closely. Some matched the bell dimensions to an impressive degree and even more could be described as very close or just close. Boston maker E. G. Wright was an interesting case, in that he made extremely close copies of the Courtois cornet bell and valve bores (a little less close through the mouthpipe), but made these cornets with rotary valves, as all of his instruments had at the time. This started around 1860, and by 1866, he started making piston valve cornets of this design. Other cornet bells, measured by the author, that can be classified as “extremely close” include Isaac Fiske, Hall & Quinby, George McFadden, C. G. Conn Besson model (and likely others), Thompson & Odell and Zoebisch. “Very close” bell copies include Boston Orchestra models, Quinby Bros., Lyon & Healy Own Make, Distin in both London and New York, Adolphe Sax, and John Heald. “Close” copies include C. G. Conn Wonder model, Boston Two and Three Star Models, Graves & Co., C. W. Hutchins, Schuster & Co., Carl Fischer and many others.

According to the New Langwill Index, Auguste Mille worked for Courtois starting about 1856 and became foreman of the factory in the 1870s. A new company was formed in 1880, “Antoine Courtois & Mille”, for a period of ten years. Antoine Courtois had no children and this partnership ensured that Mille would continue to head the shop after his employer was no longer able. Antoine Courtois died on December 16, 1881, and Mille was able to purchase the remainder of the company in 1882. Courtois’ catalog published in about 1919 stated that when Auguste Mille died in 1895, the shop was taken over by his partner, Emile Delfaux. When Delfaux died in 1908, the company was taken over by his sister Maurguerite. Miss Delfaux then took on a partner, A. Legay. Advertising during this era listed the company as “Antoine Courtois, M. Delfaux & A. Legay, Succeseurs”. The website for the current Courtois company supplies the rest of the company’s history: In October of 1917, Emmanuel Gaudet purchased Courtois and operated with business partner P. Deslaurier. Gaudet was succeeded by his son, Paul Gaudet in 1956, who then turned the company over to his son, Jacques, in 1980. At the end of the 20th century, Gaudet sold the business to JA Musik, a German company, who then sold it to Buffet Crampon in 2006. Buffett then purchased B&S, an old German maker of brass instruments and moved the production there in 2013. A fourth generation of the Guadet family was still working for the company into the 21st century, although his ownership interest in the company is not publicly known.

After a long career, importing musical instruments into New York City and Chicago, Joseph Howard Foote died on May17, 1896. The New York branch of the company was then incorporated with shareholders including members of his family. They continued to import Courtois and other instruments for several more years. William R. Gratz, who specialized in importing musical instruments from eastern Europe to New York, mostly from Bohland & Fuchs in Bohemia, took over the exclusive rights to distribute Courtois instruments in the US in 1902. As mentioned above, S. Arthur Chappell continued importing Courtois instruments into London until retirement, then turned it over to Chappell & Co.. Judging by the number of surviving instruments, sales must have been much lower than the previous decades. Within the decade, the British franchise was taken over by J.R. Lafleur & Son, who were still listing the availability of Levy, Koenig and Arban model cornets in 1913. Two Arban models are known from after 1927, indicating that there was still some demand for their old models, out of fashion for decades by then.

By 1900, Courtois’ old “New Model” cornets, orchestral trumpets, as well as the rest of their production had become old fashioned. They had a very successful niche market but were slow to modernize. Courtois cornets sold very well in the last quarter of the 19th century, despite being more expensive than others in the US market. For silver plated Bb cornets in 1885, they cost $75, compared with $65 for Boston (13% more) and $55 for a Conn (27% more). In the 1897 Foote catalog, prices had doubled ($150 for a silver plated Bb cornet), while prices of other makers remained the same, likely contributing to the fall in sales. They eventually started making more modern, long model cornets, mostly copying Besson’s designs, but as mentioned above, still had customers for the cornets that had been so highly thought of at their peak. After World War One, they updated the trumpets as well, emulating those by Besson, and judging by the number of those that have survived, were competing well in the high end trumpet market. Immediately after the second World War, this was helped by promotion in the US by Vito Pascucci and Leon Leblanc, who together established G. Leblanc Corporation and then Holton-Leblanc in 1964. They capitalized on the increasing popularity of French style flugelhorns in the Courtois, Leblanc and Holton Brands. They were slower to make trombones for the world market, but by the 1980s that they introduced American style instruments that were the most popular, not only in symphony orchestras and commercial music, but British brass bands as well. The reputation of Courtois’ instruments has continued at a high level even though they never again produced a singular design that dominated the popular market like their Bb cornets had in the 19th century.